Who is Miyamoto Musashi?

The Life and Tale of a Japan’s Greatest Swordsman.

Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645), a name that resonates with an unparalleled legacy in the history of Japanese martial arts, was Japan’s greatest swordsman and samurai. His life was not just a tale of battles won but a journey of mastering the art of kenjutsu, which culminated in the creation of a distinctive style that involves the use of two swords simultaneously. This technique, revolutionary for its time, played a significant role in Musashi’s undefeated record in over sixty duels to the death, a testament to his skill and strategic acumen.

My fascination with Miyamoto Musashi began almost four decades ago. As a karate practitioner, I was not only captivated by his extraordinary life and exploits but also profoundly influenced by his strategic insights. The lessons gleaned from his seminal work, the “Gorin No Sho” (The Book of Five Rings), transcended the boundaries of traditional swordsmanship, offering valuable perspectives that significantly enhanced my own practice of karate.

This connection to Musashi’s legacy extends into my personal life as well. My wife, who is Japanese, shares an appreciation for this legendary figure. In a gesture celebrating our respect for Musashi’s legacy and the rich cultural heritage of Japan, we named our son Iori, the same name as Musashi’s son. This name holds a special significance for us, symbolizing the values of strength, honor, and the pursuit of excellence that Musashi exemplified.

In this article, I invite you to delve into the life of Miyamoto Musashi, Japan’s greatest swordsman. The narrative is not just about his unparalleled skills in combat but also about the profound philosophy and discipline that guided his journey.

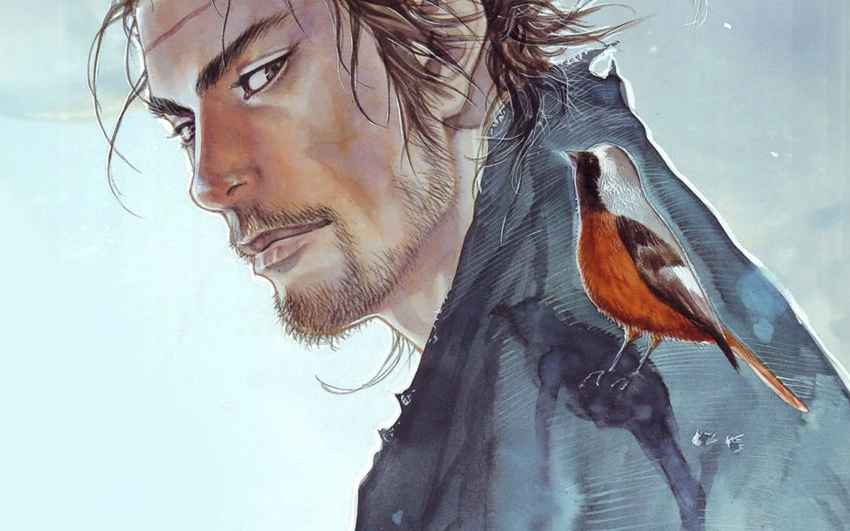

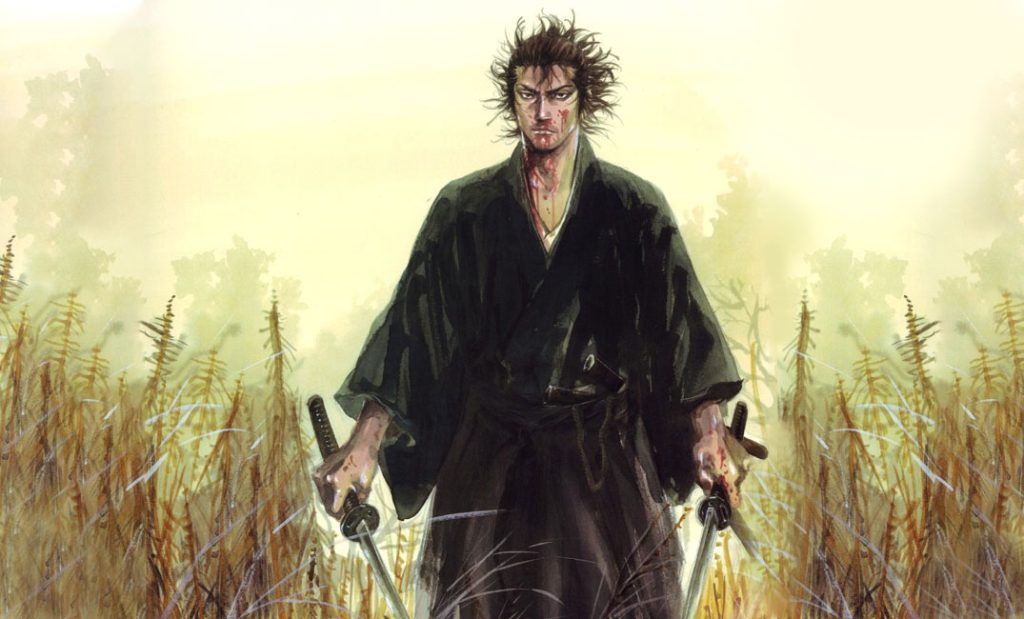

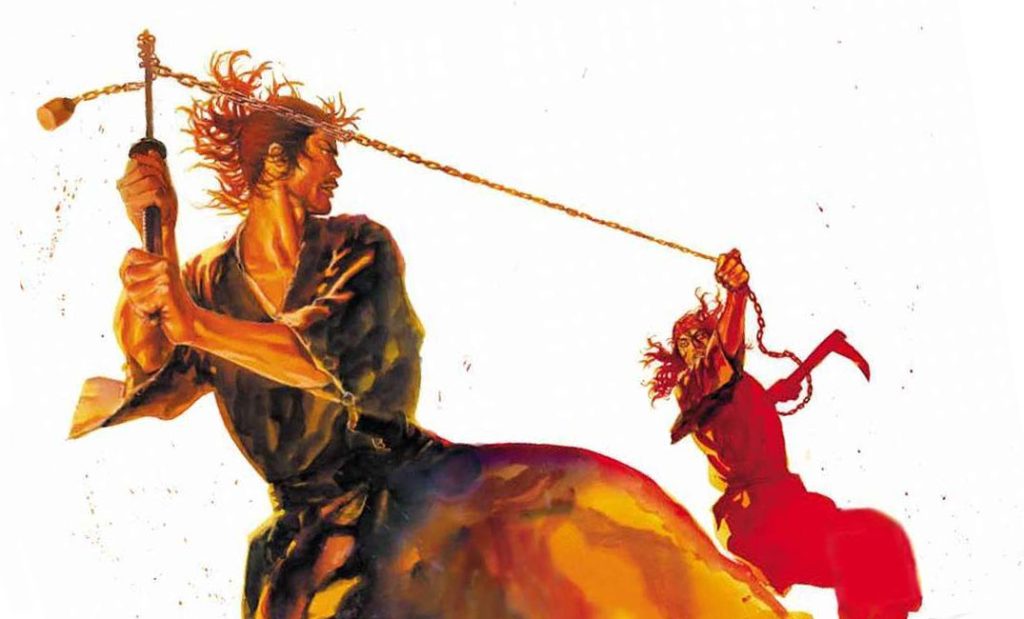

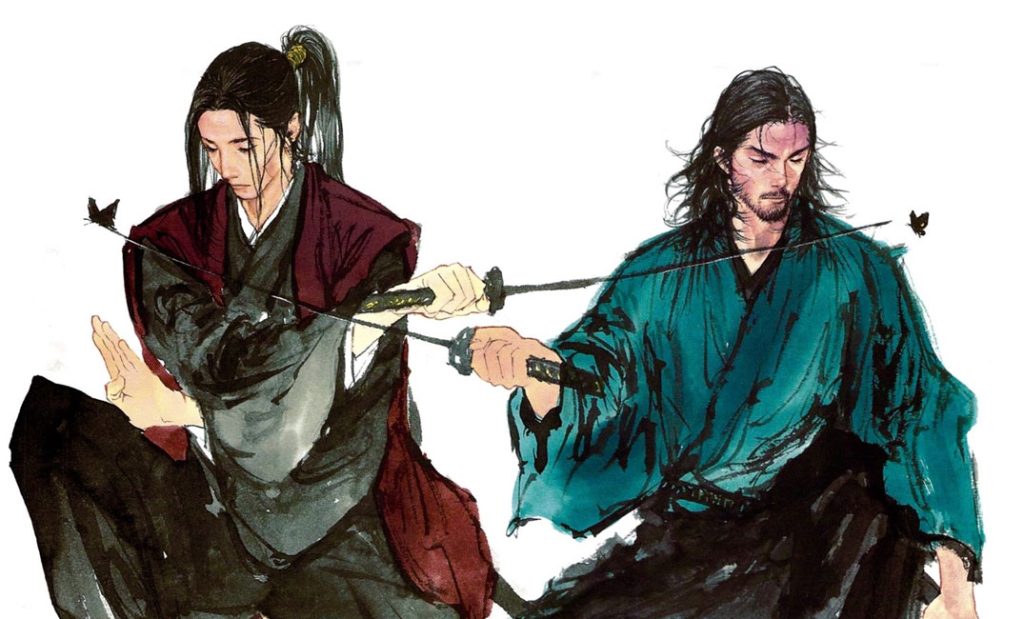

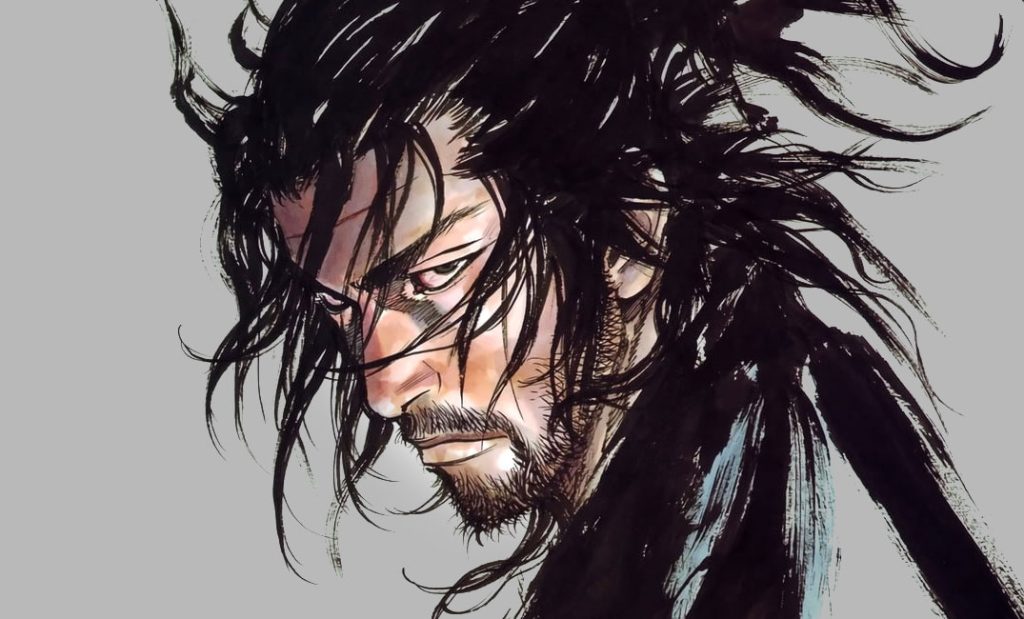

PS: The illustrations accompanying this article are from the acclaimed manga series “Vagabond” by the talented Japanese artist Takehiko Inoue.

Early life

Details about the early life of the legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi are difficult to verify as all that Musashi left behind were writings related to the Kenjutsu sword-fighting technique and strategy.

Most Japanese historians agree that Miyamoto Musashi was born in 1584 (the Year of the Monkey). That period was a time of turmoil as the country as different Warlords were fighting for supremacy over the Japanese territory.

Miyamoto Musashi was born into a samurai family in Miyamoto village, Harima province. His full name was Shinmen Musashi no Kami Fujiwara No Genshin, and his childhood name was either Bennosuke or Takezo. Musashi took his name from his birthplace, Miyamoto village.

Musashi’s father was a samurai named Shinmen Munisai, who was an accomplished swordsman and an expert in Kenjutsu (swordsmanship) and jutte-jutsu. Munisai taught Kenjutsu and juttejutsu to Musashi at a young age, as was the tradition in samurai families, and the young Musashi showed an early talent for Kenjutsu. Shinmen Munisai’s’ father, Hirata Shogen, was a vassal of Lord Shinmen Iga no Kami of Mimasaka Province.

Miyamoto Musashi’s mother died soon after he was born, so he was raised by his step-mother, a woman named Toshiko. When his father, Munisai, divorced Toshiko, Musashi was sent to live with his uncle Dorin, a monk from the Shoreian temple. While staying with the monk, he was taught Zen Buddhism and basic skills, such as reading and writing.

“Musashi had his first duel at the age of thirteen. His opponent was a samurai from the Tajima Province, a man named Arima Kibei.”

Munisai was a very harsh, strict, and demanding man, especially towards his son. Their relationship was tumultuous and Munisai showed no love for the young Musashi. It is unknown what exactly happened, but when Musashi was around 9 or 10, his father either died or abandoned the boy. Some historians say that Shinmen Munisai was killed during a duel with a swordsman named Ganryu Yoshitaka.

According to the personal details given by Miyamoto Musashi in his “Book of Five Rings”, the Gorin No Sho, Musashi had his first duel at the age of thirteen. His opponent was a samurai from the Tajima Province, a man named Arima Kibei, who was a swordsman from the Shinto-Ryu Kenjutsu school. Seconds after the beginning of the fight, Musashi thew Arima on the ground and hit him with his bokuto (a wooden sword, also known as a bokken). Arima Kibei died vomiting blood.

Musashi left the temple between 16 and 20 years old (this is unclear), to perfect his Kenjutsu technique, and followed his ambition to become Japan’s greatest swordsman.

Duelling years

Miyamoto Musashi spent many years duelling with Japan’s best swordsmen and warriors in an endless pursuit towards perfection.

The Battle of Sekigahara

On October 21, 1600, Miyamoto Musashi took part in the Sekigahara Battle, which was a war between the Toyotomi and Tokugawa clans for the unification of Japan.

Because his family was allied to the Toyotomi Clan, Musashi fought for Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s army. During the Battle of Sekigahara in July 1600, Musashi took part in the attack on Fushimi Castle (Fushimi-jo or Fishimijo). He also participated in the defense of the besieged Gifu Castle (Gifu-jo) in the Gifu Prefecture. Even at a relatively young age, Miyamoto Musashi fought vigorously, and he escaped the defeat of Hideyori’s forces unharmed.

Three years later, Musashi fought against the army of Ieyasu Tokugawa who, the Shogun Tokugawa Era (also known as the Edo period), which would last for 266 years.

After the battle, Miyamoto Musashi wandered across Japan perfecting his Kenjutsu skills, having many duels, and meeting many masters of the sword.

After disappearing from the records for a while, Musashi arrived in Kyoto around the age of 21 or 22. Upon arriving in Kyoto, he began a famous series of duels with the famous Yoshioka Clan. The clan was famous all across Japan for its Yoshioka-Ryu, a style of Kenjutsu founded around 1532 by Yoshioka Kempo.

The Yoshioka School

The Kenjutsu style of the Yoshioka Clan was part of the Kyohachiryu, which meant that it was one of the eight major Kenjutsu styles in Kyoto. The swordsmen of the Yoshioka Clan had been instructors for the powerful Ashikaga Family for four generations.

Duel 1 – Yoshioka Seijuro

Yoshioka Seijuro, master of the Yoshioka School and head of the Yoshioka family, was challenged to a duel by Musashi. Seijuro eagerly accepted the duel, and both men decided to fight outside of Rendaiji Temple in Northern Kyoto on March 8, 1604.

As a part of his strategy, Miyamoto Musashi arrived late on the day of the fight. Seijuro was greatly irritated and lost his temper with Musashi, judging his behavior to be unacceptable. As they had previously agreed, the duel was to be fought with a bokuto (wooden sword), and a single blow would declare the winner.

They faced off and took the on-guard position. In an instant, Musashi hit Seijuro’s shoulder with his wooden sword, knocking him off his feet and breaking his left arm. Musashi won the duel. With his soul tormented by dishonor, Yoshioka Seijuro retired from the warrior’s life and became a monk in a Zen order.

Seijuro’s brother, a brilliant swordsman named Yoshioka Denshichiro, became the head of the Yoshioka Family and later challenged Musashi to regain his family’s honor and avenge his brother’s defeat.

Duel 2 – Yoshioka Denshichiro

The duel was to be held at Sanjusangendo, a Buddhist temple in the Higashiyama District of Kyoto, which was famous for its thousand statues of Kannon, the Shinto goddess of mercy and compassion.

As with his last duel, Miyamoto Musashi once again arrived late to fight Denshichiro. This time, it was a duel to the death. Musashi was armed with a bokuto and Denshichiro had a staff reinforced with steel rings.

Musashi was mentally, technically, and physically stronger than his skilled opponent. Seconds after the beginning of the duel, Musashi hit Denshichiro with his wooden sword, killing him instantly with a single blow to the head.

The Yoshioka Clan had become desperate with the death of Denshichiro Yoshioka, who was now the second head of the family to be defeated by Miyamoto Musashi. The head of the clan was now the 12-year old Yoshioka Matashichiro, who, like his predecessors, also challenged Musashi to a duel. At this point, the Yoshioka clan was ready to do anything to gain back their honor and reputation. They had to take Musashi down.

Duel 3 – Yoshioka Matashichiro

This time, the Yoshioka Clan decided that the duel between Yoshioka Matashichiro and Miyamoto Musashi was to be fought at night. It was unusual for nighttime duels to be requested, so Musashi got suspicious. He arrived at the rendezvous point well before the time of the fight and waited in hiding for his enemy to come.

The boy arrived dressed in full armor with a party of well-armed retainers, archers, riflemen and swordsmen who were all determined to kill Musashi. They all hid nearby, and set a trap for Musashi, with Matashichiro acting as bait.

Musashi watched the action as he waited patiently, concealed in the bushes. When the moment was right, he left his hiding place, drew his sword, and ran towards the boy, cutting off his head. Seconds later, Matashichiro’s men gathered around Musashi, trying to stop him from escaping.

“Many historians agree that Musashi discovered the superiority of wielding two swords during this battle.”

Greatly outnumbered and with both swords in hand, Musashi cut a path through the rice fields, making his way to escape while being attacked by dozens of men. With the death of Yoshioka Matashichiro, the Yoshioka Clan Kenjutsu School was demolished.

Many historians agree that Musashi discovered the superiority of wielding two swords during this battle. The use of two swords simultaneously was totally foreign to the conventions of Kenjutsu, as samurai traditionally only fought with the long sword (Katana) held in two hands. Musashi’s experience forged the path to what would become known as the Nito-Ryu style of Kenjutsu.

Warrior’s Pilgrimage

Shortly after his series of duels with the Yoshioka Clan in 1605, Miyamoto Musashi went to Hozoin Temple in the south of Kyoto. There, he had a series of non-lethal contests with the monks, who were renowned for being masters of the spear.

He stayed at the temple for a few months, studying and exchanging fighting techniques with the monks. Musashi also enjoyed talking about Zen for hours on end with the head monk. Even today, the monks of Hozoin still train in their renowned traditional spear technique.

Historians say that from 1605 to 1612, Musashi wandered all over Japan while on a Musha Shugyo, a warrior’s journey, during which he traveled extensively to test and improve his Kenjutsu skills.

Shishido Baiken

While on his way to Edo in the autumn of 1607, Miyamoto Musashi had a duel with Shishido Baiken, a master of the kusarigama – a sickle with a chain and a weight attached to one end.

Baiken wanted to end Musashi’s reputation as an invincible duelist but was unsuccessful. Musashi struck a deadly blow first, and as Baiken fell on the floor. His pupils began to attack Musashi but quickly ran away, frightened by Musashi’s skills with two blades.

Muso Gonnosuke

Later that year, Muso Gonnosuke, a famous and arrogant swordsman, challenged Musashi to a duel. Gonnosuke was a master of the Tenshin Katori Shinto Ryu, and the founder of a Jojutsu (short staff) school known as Shinto Muso-Ryu. It was claimed that Gonnosuke had never lost a duel, and had defeated Japan’s finest swordsman. Historians say that Musashi’s father, Shinmen Munisai, had previously fought against Gonnosuke in a non-lethal duel.

“Even though Gonnosuke used his newly developed techniques, the outcome of the duel was the same: Musashi won again.”

Both Miyamoto Musashi and his opponent agreed to fight with wooden swords. Gonnosuke was quickly disabled with a single blow from Musashi’s bokuto. Strongly affected by his defeat, Gonnosuke withdrew to a Shinto shrine where he contemplated his defeat. He trained hard and developed new techniques that he hoped would eventually allow him to defeat Musashi.

Musashi and Gonnosuke dueled again sometime later. Even though Gonnosuke used his newly developed techniques, the outcome of the duel was the same: Musashi won again.

Shortly after, Musashi was about to encounter his greatest and most skilled opponent, Sasaki Kojiro.

Sasaki Kojiro, Musashi Greatest Rival

Miyamoto Musashi’s most famous duel was against Sasaki Kojiro, his greatest and most skilled opponent. It was said that Sasaki fought many duels against Japan’s best and never lost.

Sasaki developed a very effective Kenjutsu style based on the movement of a swallow’s tail in flight. Unlike other samurai who used the traditional ‘Katana’, Sasaki used a ‘no-dachi’, which was a very long two-handed sword. Despite the sword’s length and weight, Kojiro’s strikes with the weapon were unusually quick and precise. Kojiro was Lord Hosokawa Tadaoki’s private Kenjutsu instructor.

The two greatest swordsmen agreed to fight, and the duel took place on April 13, 1612, on Ganryu Island, located off the coast of the Bizen Province. The duel was set for early the next morning. On the day of the fight, Sasaki Kojiro and the officials serving as witnesses waited for Musashi for hours.

His absence leads to the rumor that Musashi had run away in fear of his life because he was so terrified of Sasaki Kojiro’s technique. Nothing was further from the truth.

“[…] he decided to arrive late at the duel to disturb his opponent’s mind”

Miyamoto Musashi was transported to Ganryu Island on a boat by a local fisherman. As part of his strategy, he decided to arrive late at the duel to disturb his opponent’s mind. During the short trip, he sculpted a wooden sword which he used for the duel against Sasaki Kojiro.

When the boat finally arrived, Sasaki and the officials were standing on the beach waiting for Musashi. Extremely irritated and blinded by rage, Sasaki Kojiro drew his Katana and threw away his scabbard. Musashi saw this gesture and said to his enemy, If you have no more use for your sheath, you are already dead.”

The dual began, and both men were on guard with respect for the other’s ability. One mistake, and it would all be over. Musashi provoked Kojiro into making the first attack and then countered quickly, breaking Kojiro’s left ribs and punctured his lungs, thus killing him.

Before running back to his boat, Musashi bowed to his downed opponent and the officials, realizing with sadness that one of the greatest swordsman ever had just died. It was at this point that Musashi attained satori or spiritual awakening. From this moment on he renounced ever doing lethal duels.

Musashi The Retainer

During the following months, Musashi Miyamoto briefly established a Kenjutsu school, but no historical records indicate where in Japan it was located.

In 1614 and 1615, a war erupted between the Toyotomi and Tokugawa families, this time with Tokugawa Ieyasu as the Shogun. Tokugawa Ieyasu saw the Toyotomi family as a threat to his rule. Miyamoto Musashi took part in warfare and siege one last time when he participated in both the winter and summer battles in Osaka.

Most scholars believe that, as in the previous war, Musashi fought on Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s side, but the exact details of his role in the war are unclear. Some believe that he joined Tokugawa Ieyasu’s army when the Shogun besieged the castle of Osaka.

Later the same year, Musashi entered the service of Ogasawara Tadanao of Harima Province as a construction supervisor. Musashi helped in the construction of Akashi Castle and helped organize the layout of the town of Himeji. During his stay, he taught martial arts, particularly Kenjutsu and shuriken throwing, and he perfected his Enmei-ryu Kenjutsu style. During this period of service, he also adopted a son named Mikinosuke.

After running his dojo successfully for a few years, Musashi’s reputation started to grow and began to be considered one of Japan’s best swordsmen. When Honda Tadamasa, the lord of Himeji castle heard about him, he ordered

Miyake Gunbei, his most skilled samurai, to go to Musashi’s dojo and show him that he was not Japan’s greatest swordsman. Musashi accepted the fight and left the choice of the weapon (either a real sword or a wooden sword) to his opponent.

Miyake’s orders were to test Musashi’s ability, not to kill him, so he decided to cut a piece of bamboo from the garden to use as a weapon. Meanwhile, Musashi wielded his bokuto. Seconds after they had faced off, Miyake Gunbei was defeated.

“After running his dojo successfully for a few years, Musashi’s reputation started to grow and began to be considered one of Japan’s best swordsmen.”

In 1622, when Miyamoto Mikinosuke, one of his adopted sons, became a vassal to the Himeji fief, Musashi started to wander across Japan again, this time ending up in Edo in 1623. While in Edo, he became friends with Hayashi Razan, a Confucian scholar who happened to be one of the Shogun’s advisors.

With the help of Hayashi, Musashi applied to become a Kenjutsu teacher for the Shogun, but his application was refused as the Shogun already had two teachers. Musashi started to travel again, leaving the capital in the direction of Yamagata City, where he adopted his second son, Miyamoto Iori.

In 1626 Miyamoto Musashi received a visit from Miyamoto Mikinosuke, his firs of three adopted sons. Mikinosuke informed him that his lord has died and that, following the tradition called junshi, he would commit seppuku (ritual suicide), following his master in death. After saying goodbye to his adoptive father with tears, he returned to Edo to follow his duty.

For a short while in 1627, Miyamoto Musashi and his second and closest addopted son Miyamoto Iori went to live in Ogura, and later entered the service of Lord Ogasawara Tadazane.

“Musashi wielded his bokuto. Seconds after they had faced off, Miyake Gunbei was defeated.”

PS: As you might know, my wife is Japanese, and we named our son Iori in honor of Miyamoto Musashi’s son.

At the end of the year, he and Iori began to travel again. It is unknown where exactly they went and for how long they travelled. They settled down in Kokura in 1634 to train and paint, staying in one of the houses of Hosokawa Tadatoshi, the Lord of Kumamoto Castle. Musashi’s main rival, Sasaki Kojiro, was a retainer under Hosokawa.

In 1634 Lord Ogasawara organized a non-lethal duel between Miyamoto Musashi and a yari (spear) specialist named Takada Matabei. As expected, Musashi won.

In 1637 Musashi fought during the Christian Rebellion of Shimabara, one of the very few turbulent events that occurred during the peaceful Edo period under the Tokugawa Shogunate. However, Musashi was injured early in the battle by a rock that fell on his leg.

His son, Miyamoto Iori, served with distinction in putting down the Christian Rebellion and was named “Advisor to the Lord”, a highly praised position.

Later Life and Death

In 1640, Musashi officially became the retainer of Hosokawa Tadatoshi, Lord of Kumamoto, and received seventeen loyal retainers at his service and Chiba Castle as his residence.

During the following year, 1641, Musashi wrote the Hyoho Sanju Go, or “The Thirty-five Instructions on Strategy” for Hosokawa Tadatoshi.

This book was dedicated to Musashi’s fighting philosophy and technique, and it would form the basis of his masterpiece, the Gorin No Sho, which would come into being two years later.

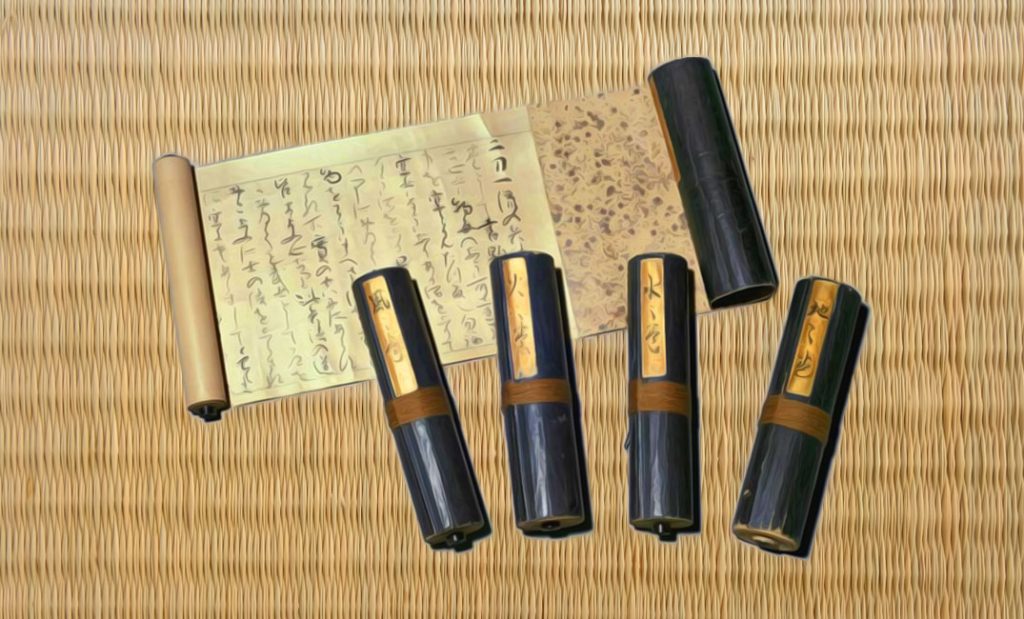

In 1642, Musashi suffered attacks of neuralgia, a painful disorder of the nerves. Feeling that his end was near, in 1643, Musashi retired to a cave named Reigando near Kumamoto to write his Gorin No Sho, or “The Book of Five Rings”. He finished it in the second month of 1645 and gave it to his closest student.

On the twelfth day of the fifth month, he finished writing Dokkodo, or “The Way of Walking Alone”, a book on self-discipline, which was intended as a guide to future generations.

He died in Reigando cave on around the nineteenth day of the fifth month, possibly on June 13, 1645.

Gorin No Sho (Book of Five Rings)

While in reclusion, Miyamoto Musashi wrote the “Gorin No Sho”, known in English as “The Book Of Five Rings”, which was a text on Kenjutsu, martial arts, and philosophy.

Many translations of the “Gorin No Sho” have been made over the years, and it enjoys an audience considerably broader than just those interested in martial arts. For instance, some business leaders find its discussion of conflict and how to take advantage of it to be relevant to their work.

The five “books” refer to the idea that there are different elements of battle, just as there are different physical and spiritual elements in life, as is believed in Buddhism.

The term “Ichi School”, which is referenced in the Gorin No Sho, refers to the “Niten No Ichi Ryu”, or “Ni Ten Ichi Ryu”, which when literally translated means “Two Swords, One Heaven”, although the translation could be interpreted as “Two Swords, One Spirit”, or “Two Swords, One Entity”.

I would greatly recommend Kenji Tokitsu’s book entitled The Complete Book of Five Rings , as it’s hands down the best book I read on the subject. Also, check out Tokitsu’s equally great book on Musashi’s life entitled Miyamoto Musashi: His Life and Writings .

The Ground Book

The Ground section of Miyamoto Musashi’s “Go Rin No Sho” (The Book of Five Rings) lays out the overarching principles and philosophy of his martial arts strategy. It’s a guide to understanding the basics, not only of swordsmanship but of any martial discipline or life pursuit. Key elements of the Ground section include:

- Understanding the Way: Musashi emphasizes the importance of understanding ‘the Way’. This refers to the path of martial arts, but it also extends to understanding the way of life and professional pursuits. He encourages the reader to learn broadly across disciplines, as this comprehensive knowledge contributes to success in one’s primary field.

- The Stance of the Sword: He discusses the basic stances and postures in swordsmanship, considering them foundational to all techniques and strategies that follow.

- The Master’s Role: There is a focus on the importance of finding a skilled teacher. Musashi stresses that true understanding of the Way can only be achieved through direct transmission of knowledge from master to student.

- Different Martial Arts: Musashi also touches upon the importance of understanding different martial arts and schools, advocating for a broad perspective that values learning from various styles.

- Personal Development: A significant portion is dedicated to the practitioner’s personal development and mindset. Musashi encourages constant practice, a commitment to learning, and a mindset geared towards continuous improvement.

- Strategy: While specific techniques are not detailed, the section lays the groundwork for thinking strategically about combat, emphasizing the need to adapt to one’s environment and opponent.

In summary, the Ground section of “Go Rin No Sho” is about laying a solid foundation in both technique and philosophy. It’s about understanding the broader principles that govern martial arts, which are applicable in various aspects of life. Musashi uses this section to set the stage for the more specific and detailed teachings in the subsequent sections of the text.

The Water Book

The Water section of Musashi’s book builds upon the foundational concepts introduced in the Ground section, delving deeper into the specifics of combat strategy and technique. Here’s a summary of the key themes and teachings in the Water section:

- Flexibility and Adaptability: The Water section emphasizes the importance of being flexible and adaptable in both strategy and technique, much like the adaptable nature of water. Musashi highlights the need to be fluid in responses and adaptable to any situation in combat.

- The Rhythm of Combat: Musashi discusses the concept of rhythm in martial arts, stressing the importance of understanding and manipulating the timing and rhythm of both the swordsman and the opponent. He speaks of the rhythm of engagement and disengagement in combat.

- Five Types of Guard: This section details five primary stances or guards in swordsmanship, each with its strengths and appropriate uses. These guards are not just physical positions but also reflect different strategic approaches to combat.

- The Gaze in Martial Arts: Attention is given to the concept of “gaze” or “eye contact” in martial arts. Musashi explains the significance of the gaze in understanding the opponent’s intentions and in controlling the flow of combat.

- Footwork: There is a detailed discussion of footwork, where Musashi describes the importance of movement and positioning in combat. He advises on how to move efficiently and effectively to gain advantage over an opponent.

- Cutting Techniques: The section provides insights into various cutting techniques, including when and how to apply them. Musashi emphasizes the need for precision, speed, and decisiveness in executing these techniques.

- Practical and Philosophical Guidance: Throughout the Water section, Musashi interweaves practical advice on swordsmanship with philosophical insights. He encourages the reader to apply these lessons not only in martial arts but also in everyday life.

In essence, the Water section of “Go Rin No Sho” represents a deeper immersion into the art of combat, focusing on flexibility, rhythm, technique, and the psychological aspects of engagement. Musashi uses the metaphor of water to illustrate the qualities of adaptability and fluidity that are essential in martial arts. This section serves as a bridge between the foundational principles laid out in the Ground section and the more advanced tactics discussed in the subsequent sections.

The Fire Book

In the Fire section, Musashi delves into the dynamics of active combat, focusing on aggression, speed, and direct confrontation. This part of the text is concerned with the heat of battle, exploring how to engage effectively and decisively. It’s about understanding when to take initiative and how to maintain control in fast-paced and intense combat situations. Here are the key elements of the Fire section:

- Timing and Initiative: The section stresses the importance of timing in striking and taking the initiative. Musashi advises on recognizing the right moment to attack, ensuring that one’s actions are both swift and decisive.

- Psychological Warfare: There’s an emphasis on psychological strategies to unsettle and overwhelm the opponent. Musashi discusses various tactics to disrupt the opponent’s concentration and confidence.

- Speed and Rhythm: Speed is a crucial element in this section. Musashi highlights the importance of varying one’s rhythm and speed in combat to create openings and exploit weaknesses.

- Force and Momentum: The use of force and maintaining momentum in combat are discussed. Musashi advises on how to apply force effectively and how to keep up the pressure on an opponent.

- Adapting to the Environment: There is guidance on how to use the surrounding environment to one’s advantage during combat, adapting tactics according to the situation.

- Types of Attacks: Different methods of attack are outlined, with a focus on direct and forceful techniques. Musashi describes various offensive moves and combinations.

- Combining Techniques: The section also deals with the integration of techniques, teaching how to seamlessly transition from one move to another, maintaining a continuous and overwhelming offensive.

Overall, the Fire section is about mastering the art of aggressive and dynamic combat, utilizing speed, force, and psychological tactics to gain the upper hand. Musashi’s teachings in this section are geared towards helping practitioners understand how to dominate and control the flow of battle.

The Wind Book

The Wind section of “Go Rin No Sho” explores the comparison and contrast of Musashi’s swordsmanship style with other schools and styles prevalent in his time. This section is crucial for understanding the broader context of martial arts during Musashi’s era and how his approach differed from and surpassed others. Here are the key points from the Wind section:

- Critique of Other Schools: Musashi critiques various contemporary martial arts schools and styles. He discusses their strengths and weaknesses, providing insight into his assessment of what constitutes effective martial arts practice.

- Comparison of Techniques: There is a detailed comparison between the techniques of these schools and Musashi’s own style. He emphasizes the limitations or shortcomings he perceives in other schools’ approaches, particularly regarding their rigidity or lack of adaptability.

- Importance of Flexibility: Musashi stresses the importance of flexibility and adaptability in techniques and strategies. He points out that many schools adhere too rigidly to their traditional methods, which can be a disadvantage in actual combat.

- Understanding of ‘The Way’: He delves into a deeper understanding of ‘The Way’ of martial arts, advocating for a comprehensive and adaptable approach over strict adherence to traditional styles.

- Avoiding Deception and Superficial Techniques: Musashi warns against being deceived by superficial techniques that may look impressive but lack practical effectiveness in real combat situations.

- Emphasis on Practicality and Efficiency: The focus is on practicality and efficiency in combat, with Musashi advocating for straightforward, effective techniques over ornate or overly complex ones.

- Personal Reflection and Continuous Improvement: Musashi encourages practitioners to reflect on their own techniques and continuously strive for improvement, instead of blindly following established schools or styles.

In summary, the Wind section serves as Musashi’s analysis and critique of the martial arts landscape of his time. It highlights his belief in the superiority of his style, not out of arrogance, but from a perspective that values adaptability, efficiency, and a deep, practical understanding of combat over rigid adherence to traditional forms and techniques. This section reinforces the idea that true mastery in martial arts comes from personal development and continuous refinement of one’s own style and approach.

The Void Book

The Void section, the final part of “Go Rin No Sho,” represents the culmination of Miyamoto Musashi’s martial philosophy. Unlike the previous sections which focus more on practical techniques and specific strategies, the Void section is more abstract, delving into the deeper, philosophical aspects of martial arts and life. Here are the key elements of the Void section:

- Understanding the Concept of ‘Void’: The ‘Void’ refers to something that cannot be seen or grasped physically, yet it is omnipresent and essential. Musashi describes the Void as the true nature of understanding – knowing what cannot be seen, touched, or easily explained.

- Beyond Technique and Form: This section suggests that true mastery goes beyond technical proficiency and physical forms. Musashi implies that the highest level of understanding in martial arts is achieved when one transcends the physical aspects and embraces the mental and spiritual elements.

- Intuitive Understanding and Perception: The Void is about developing an intuitive understanding of combat and life. Musashi emphasizes the importance of inner perception and the ability to react not just based on what is seen, but on a deeper, intuitive level.

- Flexibility and Open-Mindedness: The teaching encourages a flexible, open-minded approach to martial arts and life. It’s about being adaptable and not constrained by rigid thoughts or preconceptions.

- Emptiness and Presence: Musashi discusses the concept of emptiness – being empty of preconceptions, desires, and fears – as a state that allows for true presence and awareness in every moment, particularly crucial in combat situations.

- Harmony with the Universe: There is an underlying theme of achieving harmony with the universe, understanding one’s place within it, and acting in accordance with the natural flow of things.

- Spiritual Enlightenment: The Void is also linked to a state of spiritual enlightenment, where the distinction between the self and the universe begins to blur, leading to a profound understanding of existence.

In essence, the Void section is about reaching the pinnacle of martial understanding, where physical techniques give way to a deeper, more intuitive and spiritual understanding of the Way. It’s about perceiving the true essence of martial arts, which lies beyond mere physical movements and into the realm of the metaphysical. This section encapsulates Musashi’s philosophy that in the highest form of martial arts, one operates on a level of understanding and intuition that transcends the conventional.

Dokkodo

The Dokkodo or “The Way of Walking Alone” was written by Miyamoto Musashi one week before dying, for the occasion where Musashi was giving away his possessions in preparation for death.

It was given to Terao Magonojo, his most skilled disciple in Niten-Ichi-Ryu. After the Gorin-No-Sho, Dokkodo is the summary of Musashi’s life, his will, and his philosophy.

Author Lawrence A Kane and Kris Wilder wrote an excellent book on the subject.

The 21 precepts of Dokkodo

- “Accept everything just the way it is.”

- “Do not seek pleasure for its own sake.”

- “Do not, under any circumstances, depend on a partial feeling.”

- “Think lightly of yourself and deeply of the world.”

- “Be detached from desire your whole life long.”

- “Do not regret what you have done.”

- “Never be jealous.”

- “Never let yourself be saddened by a separation.”

- “Resentment and complaint are appropriate neither for oneself or others.”

- “Do not let yourself be guided by the feeling of lust or love.”

- “In all things have no preferences.”

- “Be indifferent to where you live.”

- “Do not pursue the taste of good food.”

- “Do not hold on to possessions you no longer need.”

- “Do not act following customary beliefs.”

- “Do not collect weapons or practice with weapons beyond what is useful.”

- “Do not fear death.”

- “Do not seek to possess either goods or fiefs for your old age.”

- “Respect Buddha and the Gods without counting on their help.”

- “You may abandon your own body, but you must preserve your honor.”

- “Never stray from the Way.”

Niten-Ichi-Ryu

Miyamoto Musashi was a lonely man who dedicated much of his life to mastering swordsmanship and Zen Buddhism. At the beginning of the 17th century, he created a unique Kenjutsu school that used both the long sword (Katana) and the short sword (Wakizashi) simultaneously.

Musashi named his two-sword Kenjutsu technique “Niten Ichi Ryu” (“two heavens as one”) or “Nito Ryu” (“the school of the two swords”). Some historians believe that Musashi was inspired to create his unique Kenjutsu style after watching the performance of the Japanese taiko drum.

Some other scholars believe that Musashi was inspired by his father’s sword-fighting style that was utilized both the Katana and the jutte simultaneously.

Since there is no fluidity of movement when both hands are used, Musashi did not support the use of both hands on the sword. He explained that if a sword was held in both hands, it would not be easy to wield it freely to either side. Musashi also objected to the use of both hands when one is on horseback or riding in marshes, fields, or among people.

Having mastered the simultaneous use of two swords, Musashi declared that his technique would considerably improve ones mastery of the Katana and Wakizashi.

He argued that if you master the art of wielding two swords, you will naturally have acquired the power to wield the long sword as well.

Musashi’s technique was totally against tradition as most swordsmen of the time were in the habit of holding the Katana with both hands. One tremendous advantage of Musashis technique was that it was sophisticated, efficient and powerful. It involved no flashy, impulsive, or unwanted movements. Another great advantage was that it offered perfect distancing and timing. Consequently, the attack would be very tight and there would be no wasteful movements.

The unique two-sword style developed by Musashi has been praised by many. The method also has several single sword techniques as well as throwing methods. For example, Musashi used to throw his Wakizashi during the fight.

It should be noted that the Niten Ichi Ryu style was designed from Musashi’s direct experience. Within this style, one can discern the passion for innovation and perfection shown by a master swordsman.

Although his method has become famous mainly because of the practice of simultaneously using two swords, it also involves techniques with the Katana (a single long sword), Wakizashi (a short sword), and the bo (a long wooden stick).

Musashi became renowned as a master of throwing weapons. He quite often threw his short sword perfectly. Kenji Tokitsu strongly believes that the real secret technique of Niten Ichi Ryu was the shuriken technique for the Wakizashi.

Today, Yoshimoti Kiyoshi continues the long lineage of the great Hyoho Niten Ichi Ryu style as a member of its 12th generation of practitioners.

Musashi The Artist

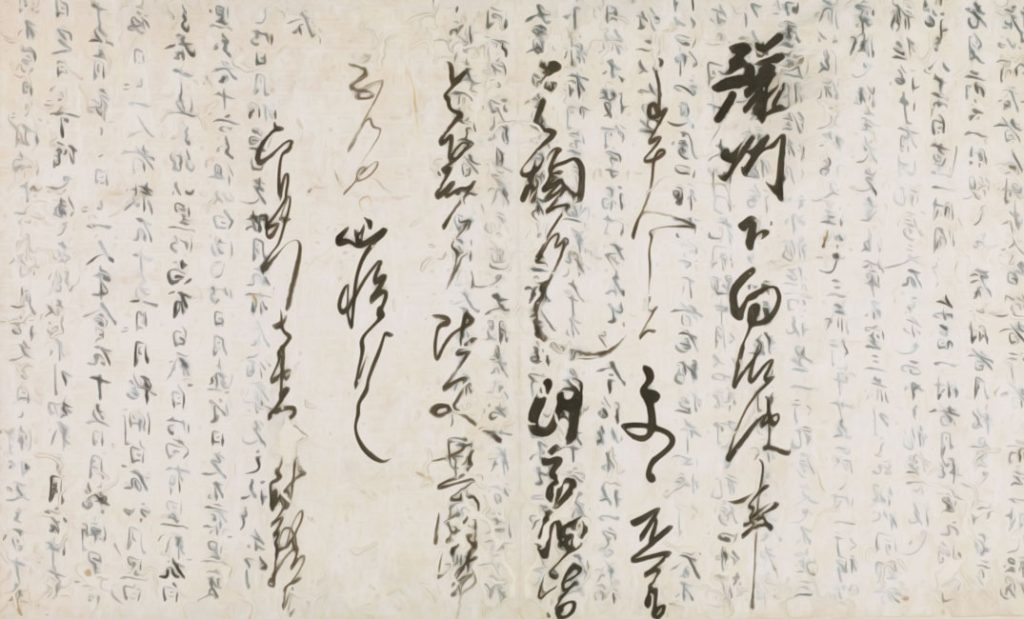

After attaining perfection in swordsmanship, Musashi turned to calligraphy, poetry, sculpture, and painting, applying his insight to these arts.

According to Musashi, if you know the Way of the Warrior broadly, you will see it in everything. His multifaceted talent is evidenced by his extant artistic works.

Musashi’s peculiarity as a painter was his powerful and direct style, as well as the amazing economy of his brushstrokes. He excelled in suiboku-ga or sumi-e (monochrome ink painting). His greatest contribution as a painter could perhaps be his paintings of birds, such as Koboku Meikakuzu (“Shrike on a Dead Tree”), and Rozanzu (“Wild Geese Among Reeds”).

Later in life, Musashi said in his “Gorin No Sho” that he didn’t feel the need for a teacher in any field when he applied his principle of strategy to the Ways of various arts and crafts. It was by creating calligraphy and classic ink masterpieces that Musashi proved that idea.

What characterizes his paintings is the efficient use of ink washes and his unique and economical way of using brush strokes. He became a master of the “broken ink” school of landscapes, and he later applied this technique to other subjects in paintings, as can be seen in “Koboku Meikakuzu” (“Kingfisher on Withered Branch”, which was part of a triptych of which the other items were “Hotei Walking” and “Sparrow on Bamboo”), “Hotei Watching a Cockfight” and “Rozanzu” (“Wild Geese Among Reeds”).

Please click here to see Musashi’s artwork.

PS: He is a picture of me , in a temple in Nagoya, Japan, with two original pieces made by Miyamoto Musashi himself. During Musashi’s time, the temple has a hotel where he stayed. He donated these two artworks as a mean of payment for his one month stay.

Conclusion

The life and teachings of Miyamoto Musashi extend far beyond the realms of traditional swordsmanship, offering invaluable lessons for practitioners of various martial arts, including karate. Musashi’s approach to combat, characterized by adaptability, strategic foresight, and a deep understanding of the opponent’s mind and intentions, aligns seamlessly with the principles of karate.

For us as karate practitioners, delving into Musashi’s philosophy and techniques is not just about learning new combat strategies; it’s about enriching our understanding of martial arts as a whole. Musashi’s “Gorin No Sho” (The Book of Five Rings) is much more than a treatise on swordsmanship; it’s a guide to discipline, mindfulness, and the pursuit of excellence. These principles are fundamental to karate and can significantly enhance our practice, both in the dojo and in our daily lives.

Studying Musashi’s life and works encourages us to look beyond the physical aspects of karate and explore the mental and strategic components of martial arts. His teachings remind us that true mastery comes from a balance of physical skill, mental acuity, and an unwavering spirit—a harmony that is at the core of karate.

As karate practitioners, we continuously strive to improve not just our techniques, but also our mental fortitude and understanding of the martial arts philosophy. Embracing the wisdom of Miyamoto Musashi can lead to profound personal growth and an enhanced practice. His legacy, therefore, serves as a timeless source of inspiration and a beacon guiding us towards the path of continuous improvement and excellence in our martial arts journey.

Resources

If you like the article you just read and just became a fan of Miyamoto Musashi, let me propose to you a list of my favorite books, manga, anime and films. And YES, I read and saw them all!

Books, Manga & Novels

- Musashi (novel) by Eiji Yoshikawa.

- Musashi: A Graphic Novel by Sean Micheal Wilson.

- The Book of Five Rings: A Graphic Novel by Sean Micheal Wilson.

- Vagabond (manga) by Takehiko Inoue.

- Miyamoto Musashi: His Life and Writings (book) by Kenji Tokitsu.

- The Complete Book of Five Rings (book) by Kenji Tokitsu.

- Musashi’s Dokkodo (book) by Lawrence A Kane and Kris Wilder.

Films & Anime

- The Samurai Trilogy with Legendary actor Toshiro Mifune.

- The Ultimate Samurai – Miyamoto Musashi with actor Kinnosuke Nakamura.

- Miyamoto Musashi (tv drama) by Kimura Takuya.

- Shura No Toki (anime series) by Shin Misawa.

- 10 Ways Meditation can Improve Your Karate - March 6, 2024

- Is Tai Chi Effective for Self-Defense? - February 16, 2024

- Do You Need to Add Ground Grappling Into Your Karate? - February 15, 2024